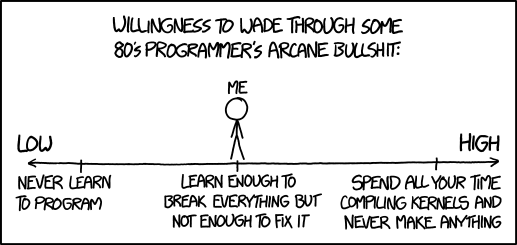

Dealing with arcane bullshit

Being a young scientist, at times I find myself having to deal with some programing related arcane bullshit. This post is something I wanted to write about for a while.

Case 1: video stimuli

The primary culprit in this case is Presentation software from Neurobehavioral Systems, which, fittingly for its name, is a software for rigorously timed stimulus presentation. To be clear - it’s a very good, very reliable program and it has been serving our lab well for several years. It allows for frame-perfect presentation of visual stimuli, playing sounds, creating logs and synchronising with other lab equipment. It has its quirks though. And given that many problems can be solved by bashing one’s head on the keyboard long enough (i. e. by spending lots of time reading the documentation and trying things out) I have earned a reputation within our lab for making Presentation work.

One of the things I had to deal with was playing video. The features list states that it can display compressed video using any DirectShow compatible codecs installed on your system. In practice, only after trying to play some file given to you by your colleague do you realise that only .avi container can be opened. And after converting to .avi things still fail, with a cryptic error message about calls to DirectX going wrong.

The solution comes from a semi-official wiki, on which the video page is immensly helpful. The problem is due to codecs. First, you should ideally be using x264, because it’s tried and tested. Second, you need to have ffdshow software installed on your PC to ensure that those codecs are available where they are needed (your video player working does not mean Presentation would work too). And as a cherry on top, you need to override some system settings. So you keep telling yourself that you are a serious scientist while you get flashbacks of the 2000’s as you download and launch a somewhat shady looking program called Codec Tweek Tool (to make things even more arcane, the wiki specifically tells you to get version 6.1.1 because later releases removed the required functionality). Afterwards, things begin to work.

As a side note, for my current study I need to prepare mp4 files by cutting, resizing, removing audio and converting. My tool of choice is ffmpeg and I keep the following command as a very precious note, maybe it comes useful for somebody else too (the -strict and -experimental flags seem essential for good video quality; -ss and -t are for selecting the right fragment, -vf scale=... scales and -c:v selects the codec):

ffmpeg -ss <start time> -i INFILE.mp4 -t <duration> -vf scale=1440:1080 -c:v libx264 -an -strict -experimental OUT.avi

Case 2: port codes in Recorder

Second example involves an interface between Presentation and Brain Vision Recorder, again an established and reliable software, used for EEG and other physiological recordings. In many experiments, we mark the presentation of stimuli in the EEG signal by sending markers over an LPT port (essentially using an old printer cable). In Presentation, the experimenter simply needs to assign a number (port code) from 1-128 range to a stimulus.

Behind the scenes, in technical terms, the LPT port has 8 signal lines (8 pins used to send signals) which can be switched from low (0 volts) to high (5 volts) state for several milliseconds with negligible latency. This allows for sending port codes in binary format, so for example number 21 is represented by pins 0, 2 and 4 (I am counting from 0) being set to high, because 21 equals 2^0 + 2^2 + 2^4.

However, by default, Recorder uses only pins 0-3 for stimulus markers, and pins 4-7 for response markers. Therefore, it interprets the above input as Stimulus 5 (2^0 + 2^2) and Response 1 (2^0 as pins 4-7 are counted anew) ocurring at the same time. Such behavior can be useful, can be changed in Recorder’s menu, and is described in Recorder’s manual, but can be extremely confusing when all you have is a recording where markers are all wrong. And it has caught out several of my colleagues already and gave us a bit of a puzzle for the first time it happened. Turns out that binary representations are useful in life.

Case 3: inhouse USB-too-USB

Speaking of interfacing, there was a time when we had to send some markers through a COM port (a different kind of port, which in this case allows sending pieces of text) using an inhouse USB-to-USB connector. The receiving program (also inhouse) required messages to end with a new line, windows style (which is actually two characters from the ASCII table, “carriage return” followed by “line feed”, usually represented as \r\n). And while Presentation interprets the \n symbol correctly, for some reason it would not accept the \r typed in the script. Luckily, it accepts hexadecimal codes, so the solution was (if I remember correctly) to type it in as \x0D\n (0D in hexadecimal translates to 13 in decimal or 00001101 in binary, which is the ASCII code for “carriage return”). I believe that many people would classify that as an obscure piece of knowledge.

Case 4: explicit mask in SPM

Another example: some time ago I was trying to use the explicit mask option in SPM (arguably the most popular software for fMRI analysis), but got a strange error. The explicit mask is neither a standard, nor a very uncommon setting. After spending hours trying to find an error in my data I tried the same on my colleague’s computer, and it worked out of the box. However, he had an older version of SPM. Working from there I could check the source code (luckily that’s possible for a toolbox created in Matlab) and locate the error. Only then did I find out that the solution had been posted several months earlier on the SPM’s mailing list (but for that I had to search the topics on the mailing list for mentions of the offending function, googling the error message before yielded nothing of use). This was SPM12 revision 6906, published in October 2016 and replaced by revision 7219 in November 2017. For a year, the fix had to be downloaded from a mailing list (or done manually, as it was pretty much a one-liner).

Case 5: multiple displays

The final example is related to HDMI cables and still remains a bit of a mistery to me. In our ongoing experiment we needed to show different things (including picture from a GoPro camera) at different screens at different times. One iteration of our setup (luckily replaced by a more efficient solution) used an HDMI splitter (sends one input to two screens) and had us swap out the cables manually. We found out that after plugging in a cable, we sometimes got the image on one screen, sometimes on the other, and sometimes, seemingly at random, on both (the way we wanted). It turns out that the workings of HDMI are more complex than we initially thought. I don’t know the details, but after the connection is made, the computer probes the output devices for their display parameters and adjusts accordingly. If the devices on the other side of the splitter are different, it might get a response from either of them, thus leading to unexpected behaviour (thanks to Alex for pointing that out when we discussed our options over e-mail).

Summary

What’s the moral of all the stories? Apart from the fact that when using different pieces of software and hardware together one should expect things to go wrong and that documentation for scientific software may or may not be lacking it is this: more people should learn things like what ASCII is and how numbers are represented in binary. It does come useful.